What a lark! What a plunge! For first time readers of Virginia Woolf...

A few pointers.

This post is for people who are new to Virginia Woolf’s writing or who have tried and struggled to read her before. You will see, from what I’ve written elsewhere, that I had a rather rocky start with Woolf myself – the penny didn’t drop for years.

I’ve written these pointers with Mrs Dalloway in mind (which we will be reading in June). Needless to say, skip this if you’re an old hand.

1. What the bleep. What’s going on? I’m lost.

If you are very clever and not at all clueless like I was when I first tackled Mrs Dalloway, then perhaps you are not lost and can skip to point 2. For the rest, please don’t worry if you are momentarily disoriented. It is only that we are inside Mrs Dalloway’s quick-leaping mind and it’s streaming off in all directions as minds do. She is thinking about the weather. She is thinking about her youth and the house she grew up in. She is thinking about poor Mrs Foxcroft and admirable Lady Bexborough who both lost sons in the War. She is noticing the ducks at St James Park. She is self-conscious about her hat. Just roll with it.

2. Notice the rhythm and pace.

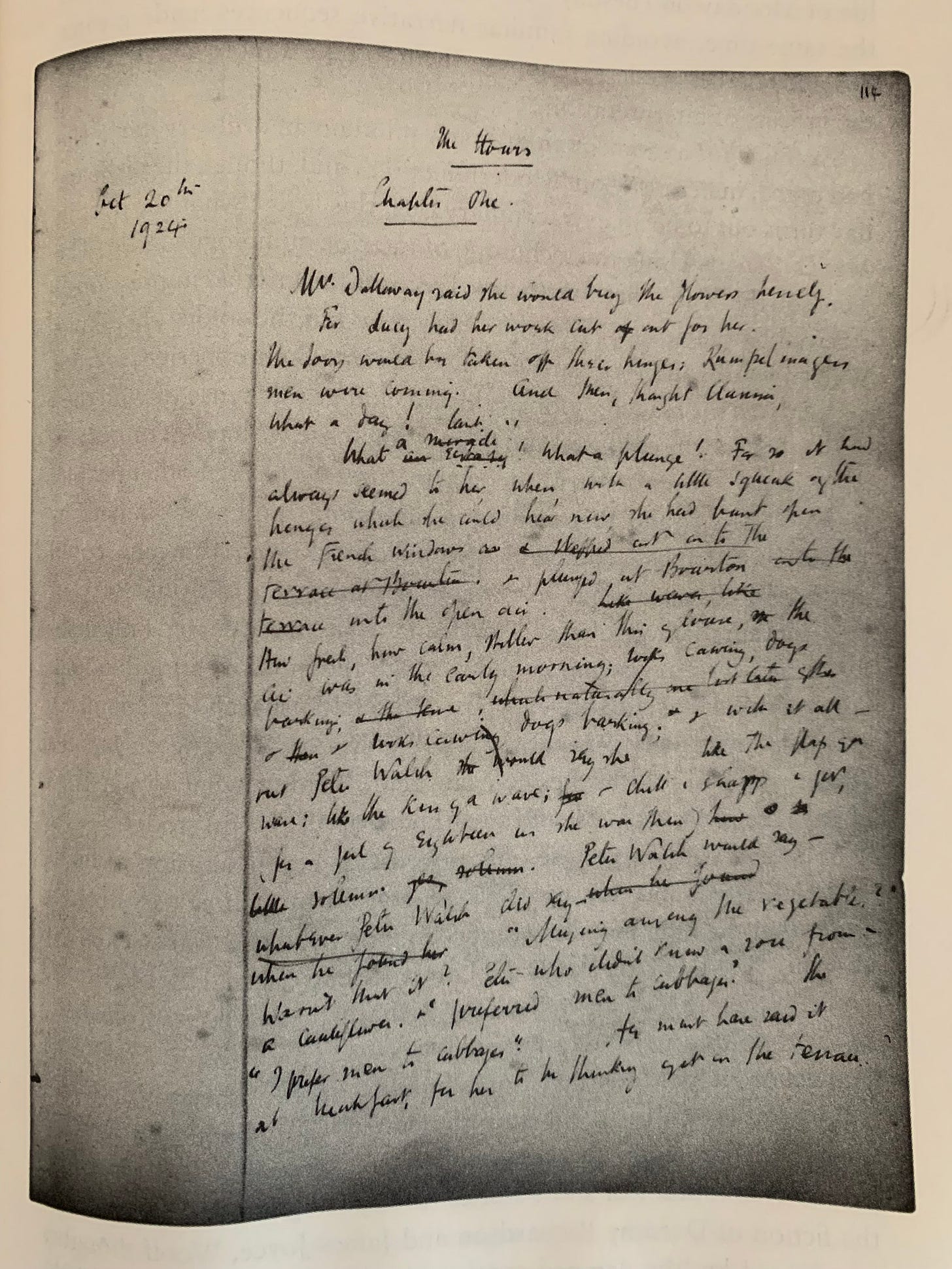

Woolf’s writing is so invigorating! We are off at a fast clip from the very first words. What a lark! What a plunge! The writing at this point is choppy and quick, an effect enhanced by long tumbling sentences broken into shorter subclauses and lists. Opinions, impressions, and fragments of memory all intermingle. Consider reading the first five pages aloud to yourself. Listen to the quick, bright cadence and inevitable breathlessness that accompanies the long chains of associations joined by commas and semi-colons. The tempo will change at different points in the story, but we begin allegro.

3. The questing, jumping, circuitous mind is central (not secondary to ‘the action’)

Mrs Dalloway is a portrait of interiority. The first time I read it I didn’t understand this and so became quickly frustrated and bewildered. It felt as if the novel’s narrative voice was perpetually sidetracked away from the main action. But this is wrong. The questing jumping, circuitous narrative voice is the main action. It is the story. We are spending a day inside the heads of Clarissa Dalloway and Clarissa’s opposite number, Septimus Warren Smith, and a number of supporting characters and even a few minor characters who pop up, burn brightly, then disappear, never to be heard from again.

4. Approach Woolf’s writing like you would poetry

Best to read as if you were reading poetry rather than prose. The most fruitful mindset in which to receive Woolf’s writing is one that is:

interested in the agility of the voice; where it pivots, lingers, leaps

open to the intermingling of past and present

receptive to rhythm, colour, imagery

indifferent to plot development.

Which is not to say that there is no plot. There is. Things happen but nearly everything is mediated through the minds of the characters. Stop worrying about the party. The party will happen later. Don’t be so impatient!

5. ‘Stream of consciousness’ does not mean unedited info dump

Woolf’s writing is sometimes described as a ‘stream of consciousness’ – a description I’ve always disliked because it connotes, to me at least, writing that is slapdash, unpolished, and boring – as if Woolf dashed off her ‘morning pages’ and sent them in, unrevised, to the publisher. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Yes, Woolf was searching for a form of writing that better captured how thoughts naturally run on from each other. No, Woolf was in no way slapdash in her approach to writing. The apparent stream of consciousness that you will notice in Mrs Dalloway is an effect, not an indication of how the writing was done. (I will have more to say about stream-of-consciousness writing in a later post.)

6. This is a story about everyday experience

Mrs Dalloway is a story about ordinary people during a single day in London in June. In Virginia Woolf: An Inner Life, Julia Briggs says that Woolf wanted Mrs Dalloway ‘to bring the reader closer to everyday life, in all its confusion, mystery and uncertainty, rejecting the artificial structures and categories of Victorian fiction.’ In other words, it was possible to write about ordinary people. Writers need not only concern themselves with knights and villains and kings and all the rest.

7. Don’t try too hard. Just allow yourself to be carried along

The pointers above are intended to help you find your way in, but in the end it’s a novel not an academic exercise. It’s there to be read and to be lost in. Losing oneself in a book is one of life’s great joys!

Don’t overthink it. Just dive in. Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Thank you for writing this. I feel less lost now and encouraged to keep reading the next pages!